The interior decoration of St Andrew’s marks it out as special and, more than anything, accounts for the church’s listing as Grade II*. Almost every surface is decorated with murals, and stained glass fills every opening on the north, east and west sides of the building. The windows on the south side lost their coloured glass when a V1 rocket landed nearby.

The richly decorated interior is outstanding for the coherence of its design, even though its execution was spread over more than 30 years from 1886, two years after the church was consecrated, to 1919 when the last of the painting was completed.

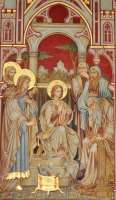

A scheme was worked out by the architect, Sir Arthur Blomfield, in conjunction with Heaton, Butler and Bayne, the foremost church decorators and stained glass craftsmen of the late Victorian era. Robert Bayne was responsible for the design and one man, Alexander Higerty, painted all but one of the murals. Bayne, who had a long grey beard that forked at the end, was known for incorporating self-portraits. He almost certainly looked like the king with the box of jewels in the depiction of the baby Jesus in the stable at Bethlehem and is probably the bent old man on the right in the picture of the young Jesus teaching in the temple.

Blomfield designed the pulpit and it was carved from local stone in Malta. The architect also designed the font with its elaborate carved wooden cover. Unusually, the font was originally placed at the front of the church, blocking the view of some of the congregation and generally arousing concern in case the pulley system failed and the heavy canopy came crashing down. In 1891, it was moved to the west end of the church and a baptistery was created.

The paintings and windows are characteristic of the Arts and Crafts movement which admired all things Gothic, as shown in the ecclesiastical arches which provide the settings for all the paintings and in details such as the tiled floors on which most of the stained glass saints stand. This makes the garish 1966 window of the Virgin and Child glaringly out of place.

The lancet windows in the nave represent apostles and saints, with the exception of the Virgin and Child which replaces an earlier version of the same subject. The nave paintings, on the other hand, work in chronological order from the north east arch, depicting the Annunciation, to the south east arch, showing Jesus’ ascension into heaven. At the east end, on both sides, water has badly damaged some of the murals but, for the most part, the rest are in excellent condition, though in need of cleaning and minor conservation work. It is uncommon to find church paintings from this period that have not been overpainted, often to their detriment.

Such damage will not recur, following the re-roofing of the north and south sides of the church in 2015 and 2018, generously funded by the The National Heritage Lottery Fund, the National Churches Trust, the Diocese of London, the AllChurches Trust, the Wolfson Foundation, the Stuart Heath Charitable Settlement, the Grocers’ Company and the government through the Listed Places of Worship grant scheme which repays VAT on repairs.

The scheme in the chancel is more elaborate and employs different techniques. The five panels making up the reredos, with the crucifixion in the centre and Saints Matthew, Mark, Luke and John on either side, are painted on mahogany. The centre panel has been restored. Above these figures with their gilded surroundings stand figures from the early Christian church, each carrying an identifying emblem. On the north wall stands a group of Old Testament figures looking out towards their New Testament colleagues on the south wall. All these paintings, including those above the apostles, were painted on canvas in the Heaton, Butler and Bayne studio. When the congregation had raised the money to pay for them, they were glued to the walls.

The painting on the west wall, surrounding the main entrance to the church, is the only one not undertaken by Alexander Higerty. Not long after St Andrew’s opened its doors for the first time, members of the congregation raised concerns about the acoustics. Blomfield suggested a tapestry be hung along the west wall to absorb some of the sound. When electricity was finally introduced in 1906, it revealed that the tapestry was moth eaten and, like the rest of the church, filthy from gas fumes. Heaton, Butler and Bayne came in to clean the wall paintings and the tapestry was discarded.

Accustomed to the rich decoration of the church interior, the congregation found the bare west wall offensive, though the window above it was equally devoid of decoration. The solution was to paint the commandments, the Lord’s Prayer and the Credo. The work was finished in 1914, before the declaration of war, but the shields were added after, prompting the completion date of 1919. Thanks to grants from the Pilgrim Trust in association with ChurchCare and the Heritage of London Trust, this painting was conserved in 2018 and the ugly streaks of dust and dirt have been removed.

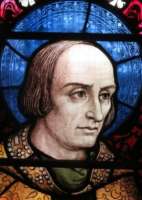

Picking up the medieval theme that runs through St Andrew’s, the Great West Window depicts figures from the early church in England, Scotland and Ireland. Most of the lancets are memorials to men who died in World War I.

The Great East Window is by the noted Scottish stained glass artist William Wilson and was installed in 1951. It picks up the themes from the reredos beneath it and shows the crucifixion with scenes from Jesus’ life in the lower panels and the four evangelists above. A depiction of Christ the King, holding the flag of St George surmounts the crucifixion.

Here is a section of the west wall before and after conservation.

Before restoration

Before restoration

After restoration

After restoration

Mark Perry working on a section of the painting: